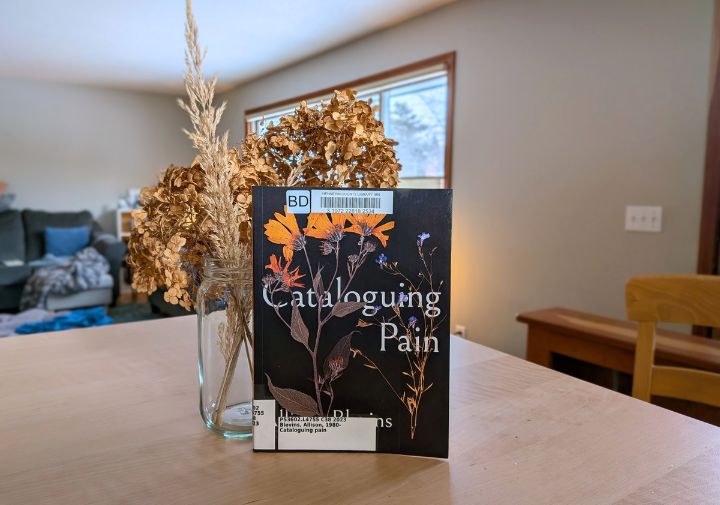

Book Review: Cataloguing Pain by Allison Blevins

Cataloguing Pain (YesYes Books, 2023)

Allison Blevins’ Cataloguing Pain reads like a worship of pain, which is a nod to the poet’s ability to morph agony into pleasure by shaping and re-shaping language—how, in a poem in which the speaker recalls that first “small burning” of desire between her thighs when she was a child thinking “just right about that girl on TV,” the only solution “was to rub the pain away.” (from “Pain as Caged Birds”)

In the same way, Blevins defines and re-defines pain, as she knows it—how eventually the physical pain felt in a disabled body fades against the anguish of remembering what the body once did and is no longer capable of:

The pain scale is no longer body or nerves: my locking hips, my tightening calf. Pain is memory. Pain is how my children used to run their bodies full speed into my body, the shush of an elliptical machine, that night we fucked on the living room floor of our first house. (from ‘Diagnosis’)

While pain presses on the body, demanding to be felt, in the first half of the collection, it finds a way to settle in the second half. The pain is still there, but in a coexistence with the body, even finding ways to bring gratitude and moments of joy into the speaker’s life. In one section of “Pain as Caged Birds,’’ Blevins turns physical therapy on an underwater treadmill into a cinematic love story:

We could almost be mistaken for lovers nearly in love if a camera would swirl around us. We stand face-to-face, hold hands gently over the water. The audience dizzies from the spinning. I imagine some film school professor once associated vertigo with love and now here we are.

Again, that collision of pleasure and pain. How they can be felt simultaneously, how one can breed the other, how one cannot be felt without the other, “how skin softly hardens at the heels and elbows, the first crunch of cinnamoned sugar on toast in the mouth, jumping bones that bend and run on landing . . .” (from “3 am on the toilet, the shell forgets”)

I feel like this idea comes to a poignant peak in “Running as Self-Portrait,” where running becomes a metaphor for living in a body with chronic pain: “I’m the running [. . .] We who worship at the feet of pain have been cured of before and after.”

“Cataloguing Pain as Non-Narcotic Pain Reliever” feels like the poem where the pain settles, drifts to the background, overridden by joys so great, they’re akin to pain:

Each of my children fed from my breasts, wrapped their tight hands tight around my index finger as they tippled and dozed on my belly. This is the tight I feel. Not the electric pain of information pulsing over batter nerves, pain that bands my legs and chest—the memory of my children squeezes me.

The memory of her children doesn’t hurt or soothe; it squeezes—an ambiguity that could fall in either direction.

What I love about this collection is that it does not call the reader to understand the speaker’s pain. Similarly, it does not preach gratitude through pain or offer a guide toward relief for those experiencing chronic pain. It merely asks the reader to bear witness:

Someone must witness the chrysalis, the knife, how it burns to expand and dry and shake in the shell. (from ‘Cataloguing Pain as Non-Narcotic Pain Reliever’)

Learn more about Allison Blevins at allisonblevins.com .